Then,

when is something not feminine?

Should art be considered feminine just for having a female artist?

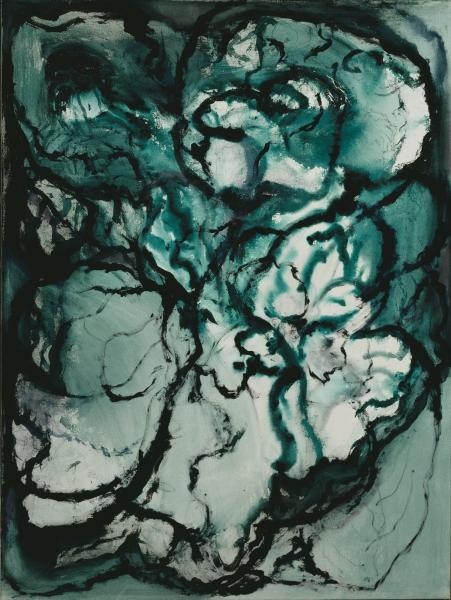

Cauliflower is an adventurous abstraction that is still somewhat tethered to representative art through a whimsical and fitting name. The dragging contours of leafy acrylic on the canvas, over the soft ghostly whites and green really are vegetable-esque. Sterne is able to perfectly extract (or harvest) the necessary visual information required to identify a mass of curves as a cauliflower. It is vegetable-esque, but there’s nothing on the canvas that would make this piece woman-esque.

Nevertheless, while not a work that is feminine on its own, you could say ‘Cauliflower’ was feminized. Hedda Sterne was known to be the only woman in a group of male artists: the Irascibles. Sterne, in a photo of the group, stands above a group of suited men in a dress. The singularity of her gender in this photo is tied to Sterne’s career as an artist as often as her genre of art.

It’s a bit insulting to the artist’s philosophies, though, to only look at Sterne’s artwork as foremost a woman’s work. The artist’s foundation, when introducing the artist, has explained, “She was asked often enough about the photograph that she would later express bewilderment: she would tell an interviewer, ‘I am known more for that darn photo than for eighty years of work. If I had an ego, it would bother me.’”

Hedda Sterne, Cauliflower, 1967, synthetic polymer: acrylic on fabric: canvas

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Madge Blumencranz, 1975.84

The Justifications Behind this Archive

The interest in the mutability of femininity across genders isn’t a direct theme of many works, but it is a tying narrative that occurs because of the power dynamics that must be negotiated in Feminist art history. It is a common individual sign, though, as women (and, to a lesser extent, other feminine figures) are regularly subjects of artworks.

In the art world, there have been some recent, well placed considerations of gender, and women artists. Some important recent showcases included the national tour of Kara Walker’s work, which made a stop at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in 2017, entitled, “Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated).” Walker, of course, is known for her historical work that dissects the aesthetics of American anti-blackness and misogynoir, in particular. This exhibit focuses on gender as it is composed of works that challenge how black women, historically, have been caricatured. In 2016, SAAM hosted “The Art of Romaine Brooks”, with guest commentary from Joe Lucchesi; Brooks’s art is at times both cutting-edge and playful with its portraiture, depicting dandy women and arrogant aristocrats with the same keen, cold brush. While Walker’s artworks are contemporary re-examinations of historical gender and race, Brooks’s works are historic examinations of gender and class. While disregarded, or not fully examined in the past, many women artists are receiving retrospective exhibitions, and scholarly re-examinations. One of these events occurred at the National Portrait Gallery: the gallery’s exhibition on Hung Liu, entitled “Portraits of Promised Lands” curated by Dorothy Moss. The retrospective is remarked to be important in some promotional pieces, as the National Portrait Gallery’s first solo retrospective for an Asian woman. A similar retrospective was the 2016 Denver Art Museum “Women of Abstract Expressionism” exhibit, curated by Gwen Chanzit. This exhibition covered much more ground than Hung Liu’s, which was focused on a single artist; Chanzit was able to recenter one of America’s most prominent art movements to the women who have been neglected equivalent appreciation as their male peers in posterity. These latter exhibitions weren’t thematically on gender in the same way as the former two: they are works that are connected to womanhood, not by the theme of the works, but by the gender of the artists. Exhibits are made to be about women (and, possibly, femininity) in two ways: they largely depict women, or they are centered on women artists.

The most obvious venue for discussing gender in art history would be The Woman’s Art Journal. This journal primarily collects reviews and original articles that use Feminist interpretations for art history of all art eras. Some recurring topics of its articles in recent years have been examinations of works of women artists, the marginalization and devaluation of these artists in history and curatorial spaces, and much more rarely, women as subjects in art. Men, going off of abstracts, have been discussed as subjects in works in this journal as much as women. Particularly, male nudity is often examined in relation to a woman artist, or as something disempowering to men. One such piece was Aliza Edelman’s “Eunice Golden's Male Body Landscapes and Feminist Sexuality” which mapped the lack of institutional success, despite her popular success, to the taboo subject of her art. Lauren Jimerson, a few years prior, would also document a woman artist crossing societal lines in painting male nudes, in her work “Defying Gender, Suzanne Valadon and the Male Nude.” Male portraiture, in this journal, is often related to male nudes by women artists; portraiture of women is examined in many more styles. But, this shows a threat to hegemonies of gender in its discussion. An examination of the gender-non-conforming Constructivist Marlow Moss was also fairly recent. Through this journal’s Feminist art historical lens, discussions of femininity are, somewhat obviously, connected to discussions of power dynamics. Which, of course, are shown to be challenged in some way, through an artist’s work

Femininity is not solely trapped within womanhood, and womanhood is not only understood through femininity. A relationship between femininity and womanhood exists, but equating them is deeply limiting. The pieces chosen aren’t necessarily political pieces about gender. They each show a particular relationship of gender to femininity. This is sometimes direct, from the artist to their subject--and sometimes indirect, from an artist to their place in history. In a few places, it is a new framing of a given piece, given contemporary understandings of gender expression. The final vision of this exhibit is to provide no unified vision of gender expression. It hopes to highlight the lack of gender cohesion that exists, already, in art history.

Room 0 Room 1 Room 2 Room 3 Room 4

This is a website by Elise. Thanks for looking at my fake art exhibit : ).

Notes